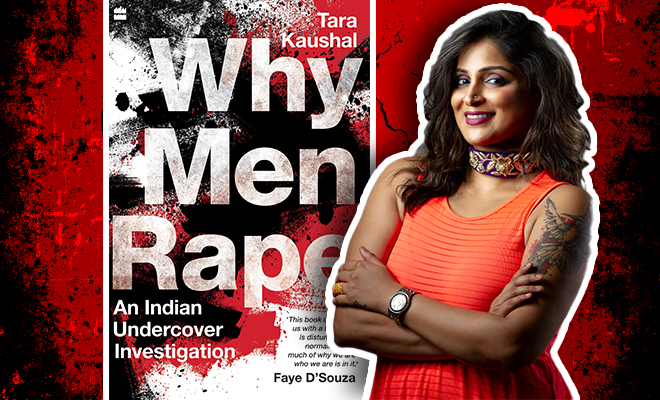

Tara Kaushal, Author Of Why Men Rape Gives Us Bone-Chilling Insights Into The Minds Of Sexual Offenders

We live in a culture where parents get anxious if their daughter is running late and their minds run to the worst possibilities. Most of us have been told to cover up, to not go out late or to not speak to too many boys, as if that’s going to shield us from rape. We grow up to believe that somehow, the responsibility of avoiding rape falls on our shoulders and that there are women who make these so-called mistakes that land them in trouble. Those can include going to a party, drinking, interacting with guys, not calling your rapist “bhaiya” and basically existing? But we’ve heard of men raping children, babies even. We’ve heard of men molesting all kinds of women, irrespective of their clothing, personality, and what they do. Clearly, it’s not what has been told to us all this while. So many questions occupy our minds and we wonder why we have to alter our everyday life to feel a little safe?

I have said time and again, that to prevent rape, we have to first understand how rape culture is born and how it flourishes. Most importantly, we have to start asking questions and treat this as an emergency. This is probably the reason Why Men Rape: An Indian Undercover Investigation by Tara Kaushal and being published by HarperCollins is being called the most awaited book of 2020. This is her debut book and it’s already gained immense curiosity and is being eagerly awaited by critics and readers. Tara Kaushal received the Laadli Media Award for gender-sensitive writing in 2013-4 and her insights come from a place of immense understanding and knowledge of the issue, as I understood from our conversation. I caught up with her over a call and spent the most eye-opening 30 minutes of my life as she gave insights into the minds of sexual offenders and her experience interacting with them. Here’s the excerpt.

-

In a culture that relieves the rapists of any responsibility by victim-blaming, at what point did you decide that you had to investigate why men rape?

It was a culmination of a very long personal and professional journey. At 12, my family moved from Naval bases across the country (considered ‘safe’ spaces) to Noida. Suddenly, my parents got very preoccupied with my hemlines and deadlines. Right then, as a 12-year-old baby feminist, I started to question why the actions of men impacted the lives of women so much. It was just something that started to impact the way I thought about the world.

I studied literature with a specialisation in feminism, and have written about gender, sexuality, and gender violence for 15 years. At some point in 2013, after the Delhi gang-rape, I decided that this is the book that I have to write, that this is going to be my first book. I kept asking questions like why should I stay home if men attack women and why shouldn’t the men instead stop attacking women. To me these are logical questions, and even just the title of the book puts the onus back where it belongs… and that is on the perpetrators of the violence and not the victims of violence.

-

How difficult is it to maintain objectivity and not be overpowered by rage when you were interviewing the sexual offenders for the book?

I will not lie, it was super hard. I think I hadn’t expected just how many people, not just women, would come up to me, unsolicited, at parties or even at a tile shop. Anyone who heard I was doing this project would come to me and say, ‘I need to tell you something that I have never told anyone before… I was raped by XYZ or I was molested by XYZ.’ To me, that was one aspect that made it difficult. As much as I was happy to receive these confidences, carrying the cumulative rage — which was my rage and other women’s rage and the rage of women in general — and then going to meet men who had committed acts of violence was very difficult. I also had to be open and empathetic towards them. Because I felt that if I didn’t extend empathy to them, I would defeat the purpose of why I was studying them to begin with. If I didn’t go to them open and without judgement, then I would not understand them, I would not find the answers that I was looking for. I was very angry and also depressed at various points.

-

What impact did it have on your mental health while writing about a subject that is so overwhelming?

I started working full-time on my book in 2017 April and it was in December that I had a breakdown. I just couldn’t cope with being told of so much violence and then hanging out with these men who were committing this violence. The only thing that kept me sane during this project was the love of my spouse, friends, family and fur babies, music, and dancing!

-

Did you find anyone who showed remorse?

Most studies have shown that men who rape don’t feel guilty, especially if they are not caught. Not guilty, but, in fact, that they feel exhilarated and happy! It’s something they dwell on and enjoy as a memory. Especially men who have had no consequences for their actions… they didn’t feel any remorse and I didn’t expect them to.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_-I3vVpptk/

-

What is that one thing that you found common in all the offenders that you interviewed?

We want to see these people as demons and monsters but they live and walk amongst us. So if you feel surprised to hear that someone you know is accused of sexual violence… you shouldn’t actually be surprised. People don’t show their worst to everybody. People who commit these crimes aren’t usually those who hang around behind bushes and are waiting to pounce upon some Savarna virgin who happens along. Most people know their attackers and abusers. That’s what is common among all of them — that they are seemingly ‘normal’ men, who may be married and respectable, who live among us in society.

-

You’ve spoken about the explosion of pornography as a collaborative agent in causing gender violence. Do you think that the child or rape pornography is a cause or an effect of rape culture?

They have a symbiotic relationship but there is something known as contagion, a theme I have explored a lot in my book. Let’s take child pornography, for instance. When you start encountering child pornography, it can change your palate for arousal. And if you were attracted to kids but you were constantly reminded that it was wrong, you’d perhaps you’re your impulses under control. But when you see child pornography and that so many people are doing it, you feel you are not as much of a freak as you previously thought you were. In that sense, it allows you and enables you. Child pornography furthers child abuse.

ALSO READ: The ‘Bois Locker Room’ Chat Exposes A Deeper Rot That Comes From Gender Stereotyping And Years Of Social Conditioning

-

You also spoke about how a gang rapist didn’t believe that rape exists. Could we blame misogyny and gender-bias for this?

This particular man… I asked him “balatkaar kya hai?” and “balatkaar kyu hota hai?” and he said “balatakaar hota hai yeh bhi nahi pata.” He said, “If I see a girl in a room and have sex with her, in this day and age she won’t even go tell anyone. What has happened has happened, move on. Just no one should find out. It becomes rape only when someone finds out.”

Through the relevant religious stories, and through porn and the consequential sexualisation of society, he had come to believe that “everything about sex is normal” and that all women — even twelve or thirteen-year-old girls — wanted and had a lot of sex. Talking about Draupadi, he said that a woman has the “capacity” to have sex multiple times, so to a woman, it doesn’t matter if it is sex with one man five times or with five men one after the other. This is how he justified gang rape. “Many women are sex crazed but hide it only because of their reputations.” He took this to mean that ‘no’ from a sexually active woman was actually a negotiation, a part of the march of modernity. This subject took his gender cues from religion and pornography.

-

So he doesn’t understand the existence of consent? I don’t know what to say…

A lot of it comes from religion — or his understanding of it. For him and another one of my subjects, also a gang rapist, Draupadi was a central figure in the whole lack of understanding of consent. She seems to have more of a problem with men who won her in the game than the men who bet her in the first place. How do you expect that people who get their morals from old systems and ideologies, made by man, for man, to be able to situate the concepts of consent and rape within the human rights and sexual autonomy of the woman? In these two men’s retelling of the Mahabharata, Draupadi’s consent to marry the rest of the Pandavas never came up — and does it come up in more mainstream tellings?

Let this be a book we all read. A topic that as a country we need to delve into, understand, and react to. @TaraKaushal's ‘Why Men Rape: An Indian Undercover Investigation’, has been called “the most awaited book of 2020”, and can be pre-ordered here: https://t.co/PALcf6VVLE

— Faye Remedios (@fayeremedios) June 10, 2020

-

I believe this book can help people truly understand the problem without which it’s impossible to solve it. How do you feel about it?

The problem is huge at the moment and it’s going to get worse before it gets better. Unless there’s a political will and a grand rethink of how we’re educating our kids, it’s going to get worse. After we decide we need to solve this crisis, it will take 20 years until the boys who have been given comprehensive sexuality education in their schools come of age, and become a new generation of men. We need many more male adults in the world to have that kind of understanding and morals.

-

How does the rural-urban divide change things considering in rural areas women don’t have access to the kind of empowerment we do and sexual abuse and gender bias are more normalised?

The fate of rural women worries me a lot more than the fate of urban women. Bombay has a very high rate of reporting of sexual abuse and that’s not because there’s more abuse in Bombay. But it’s because once you’re aware of your human rights and you’re economically liberated, you will not take any shit. But in more patriarchal places, a woman won’t report even report a slap or other minor violence because that’s normal for them. It’s the worse stuff that gets reported if at all it does. The NGOs aren’t reaching and teaching the men in rural areas to stop and rethink their gender paradigm. We are not reaching the women who are in ghoongats and behind closed doors to educate them so a) know their rights and b) leave abusive situations through economic power and social support. And every time, there is a financial crisis or any crisis, women are even more disempowered because if you have money to send only one kid to school, you’ll send your son. So now after COVID, there’s an economic crisis we’re heading into and things are getting worse. Eventually things will get better, a dawn will come, but there’s a lot of work to be done between now and then.